The Gift of Grey Spaces in Our Careers

“So, what do you do?”

For over a year, my answer to this question was that I was on long term disability. But when it comes to disclosing a disability, invisibly disabled people like myself need to decide how much to share. Do I present myself authentically? Or do I protect my ability to return to work in the future?

As excited as I am to join other disabled tech employees in sharing my story for Tech Disability Project, even writing this article is a risk for my career.

Though I grew up with sick parents, it took me many years to acknowledge my own illness. Accepting and understanding my disability is an ongoing process. I don’t expect others to make that journey in the span of a short conversation.

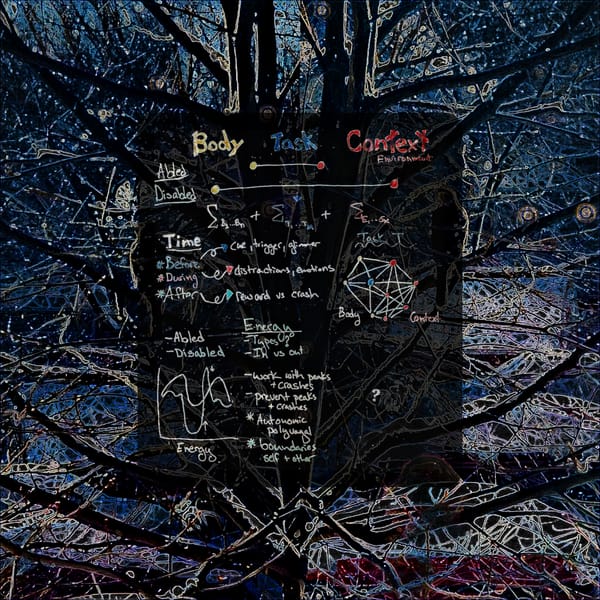

I am an assault and abuse survivor with PTSD. Due to genetics and the correlation of childhood trauma with inflammation, I also have autoimmune disease (spondyloarthropathy, colitis) and a connective tissue disorder. The systems I need to navigate as a disabled person are akin to managing additional illnesses.

The American healthcare system is unique among industrialized nations in that health insurance is tied to employment. This reality traps disabled people in jobs where they experience discrimination or don’t have access to accommodations.

Advances in our careers must be carefully balanced with healthcare, financial and accessibility needs.

I am no exception. The TNF alpha inhibitor injections that prevent my vertebrae from fusing cost $5,000 each month. If I switch healthcare plans, it could mean paying for these injections out of pocket or losing access to one or more of my providers. These fears are with the current protections for pre-existing conditions.

Over the past 2 years, my anxiety about access to healthcare worsened as I watched a possible Affordable Care Act repeal unfold on the national stage. I was unsuccessfully trying to balance advocacy with a job that was not fulfilling my need for impact or personal growth. It became hard for me to concentrate at work. I worried that being open about my experiences might confirm negative stereotypes about disabled people and female software developers. I decided to take medical leave to focus on my health.

It’s hard enough to disclose at work; it’s even harder to request accommodations and have them denied. The most frequent response I’ve received upon requesting accommodations is that it would be unfair to other employees. If I’m the only person with a private, quiet space and a standing desk, that just wouldn’t be fair. (It’s also not fair to find out you have an incurable genetic disorder at 22 years old.)

While working at a tech company that provided flexible schedules and unlimited PTO, I told my boss that I may need to come in late on certain mornings due to health issues. Though he was supportive in that initial conversation, the very next week he got upset with me for arriving at 9:15 AM. It’s difficult to open up about health issues at work only to have inconsistent workplace policies that interfere with handling them.

It’s not always disability itself, but societal constructs that make being disabled so challenging.

Given the career consequences for being openly disabled, I have yet to meet a disabled role model or mentor in tech. How can we build accessible and inclusive tech companies without talking about the real issues that affect us?

We could start by normalizing the disclosure of disability. It’s not always disability itself, but societal constructs that make being disabled so challenging. Non-disabled people are often surprised to learn that I might not always need my service dog or that many wheelchair users can walk. Disability policing — and the corresponding fear of “faking it” — not only hurts invisibly disabled and chronically ill employees, but anyone who experiences sickness or personal challenges.

Valuing career advancement above health causes many people to pursue or tolerate harmful work environments. This is certainly the case for many of us working in the hostile and competitive world of tech. Despite the legendary benefits, the tech industry has some of the highest rates of burnout and turnover.

I wish more employers would see the benefits of hiring disabled people and creating a transparent, compassionate company culture. Disabled people have played crucial roles in bringing touch screens and the internet into existence. Yet the popular narrative is that we are only the recipients of innovative technology.

I often find efficient shortcuts or see problems differently than my non-disabled coworkers. Generosity and kindness are close values because they have been essential to my survival. Being part of the disabled community has expanded my empathy for diverse users. And advocating for myself has taught me how to advocate for others.

Letting go of silence has transformed my shame into connection.

As I’ve become more comfortable disclosing, more often than not, the person I’m speaking with will share their own stories of disability or health challenges. Understanding my struggle as a universal experience helps me to integrate the collective pain of family, friends and people I’ve never even met. For me, letting go of silence has transformed my shame into connection.

So many of us hide our struggles to protect our careers. Claiming my disability and chronic illness has shown me the possibility of a more compassionate and productive tech industry. Through vulnerability and reimagining the definition of a valuable employee, I hope to expand possibilities for everyone.